People Working Together

Learning Objectives

- Appreciate the people who make local government work

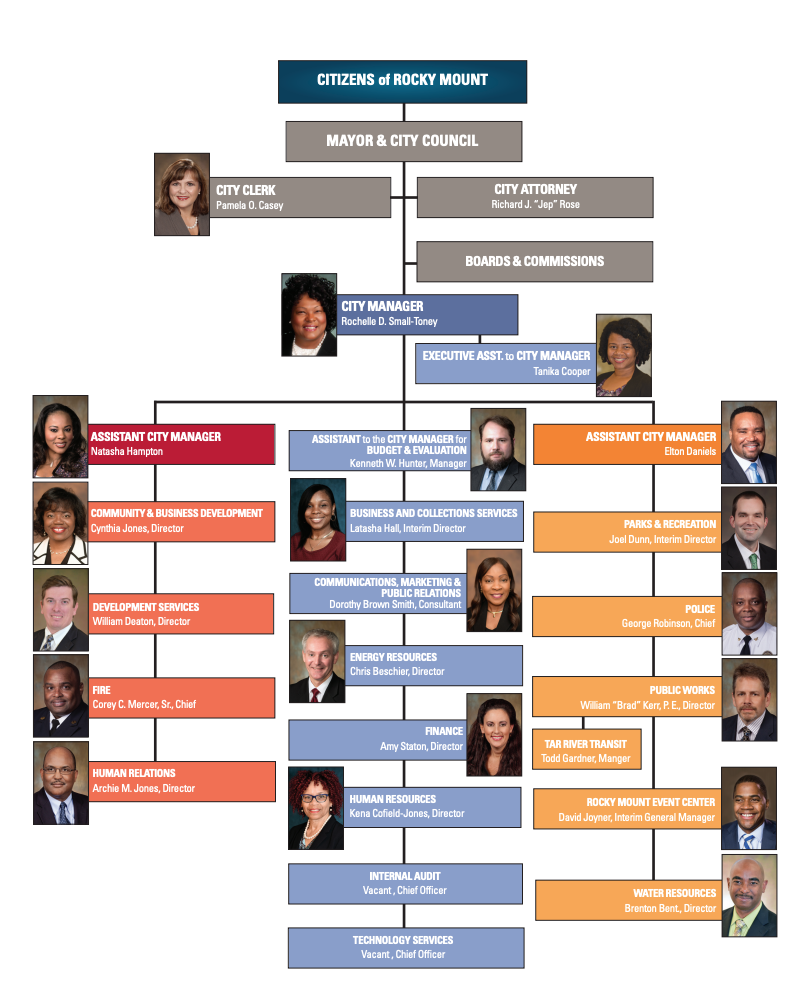

- Describe the roles of city and county managers

- Understand the importance of voting in local elections

- Identify ways in which you can engage with your local government(s)

Good government does not just happen. Rather, it is the result of people deciding what needs to be done for the community and then working together to carry out those decisions. People make government work. Who are the people involved in local government?

Many people may be unaware of how they shape local government policies and services. Residents, shoppers, workers, travelers, visitors–everyone uses local government services. And we–the general public–influence local government decisions through how we live our daily lives. It is important to understand the deliberate, as well as unintended ways, people influence public policy.

Because local government services and policies are so important to daily living, people sometimes try very hard to change them. If you want to help shape what local government does, you also need to understand how people work to intentionally change public policies.

In addition to the general public, later sections of this chapter describe four specific groups involved in the development and modification of public policy: voters, elected officials, local government employees, and volunteers, including members of appointed boards.

One person can be in several of these groups at once. For example, all elected officials are also voters. Government employees may also be volunteers in other public agencies. They are almost always voters, too. And of course, voters, elected officials, public employees, and volunteers are also part of the general public. We discuss the groups separately to indicate the different ways people help shape the way government works.

Unintentional Public Influence on Policy

People unintentionally influence local government policies as they use government services, through active cooperation with (or resistance to) government programs, and through public behavior that helps or harms others. Government officials often consider use of services to indicate the public’s wants or needs. According to this view, the more people use a service, the more of that service the government should try to provide.

Of course, local governments may sometimes be unable to provide more of a service, or officials may decide they cannot afford to do so. In such a situation, officials may try to limit use, but limiting use is also a government policy. For example, the more often one group of people uses a recreation field, the fewer hours it is available for other users. Government officials might respond to this increase in use by putting up lights so the field could also be used at night. They might also build additional fields so that more teams can play at the same time. These are examples of adding more services in response to increased use. But the local governing board might decide it cannot afford to add lights or new fields. It might decide to limit use of the existing field by requiring people who want to use the field to reserve it in advance, pay a fee, or join a league that schedules games on the field. These are all ways of rationing a service so it is not overused.

Cooperating or failing to cooperate with government programs also influences public policy in important ways. Many programs can succeed only if people cooperate. Consider solid waste disposal, for example. Many local governments have recycling programs to reduce the amount of waste that goes into landfills. Most of these recycling programs depend on people sorting their own trash so that recyclable materials can be collected separately from waste for the landfill. If people sort their trash, the program succeeds. If they do not, the program will not work, and officials will have to find other ways to get rid of the trash people produce.

Behavior that helps people may reduce the need for public programs. For example, if people help look after their elderly neighbors, there may be less need for county social services to provide visiting nurse services. Behavior that harms people helps shape public policy because it can create a problem that local government attempts to reduce through regulation. When some people in a community indicate that they are offended, annoyed, or hurt by dogs running loose, for example, local officials may decide that the action is so harmful that it should be regulated.

Intentional Public Influence on Policy

Talking directly to public officials is one very important way to directly influence policy. People call officials or visit them in person to discuss problems they think require government attention. They also speak at public hearings or other meetings attended by public officials. Letters to public officials or petitions signed by large numbers of people are also ways people communicate their views about what government should do.

People often organize public support for or galvanize opposition against local policy proposals. Officials are frequently persuaded by the reasons people provide in arguing for or against a proposal, but they can also be influenced by the number of people who join to support or oppose. To organize support or opposition, people publicize the problem and the response they think government should make. They often use social media to share their views with others. They may also write letters to the editors of local newspapers. They may gather petitions or organize demonstrations to get the attention of news media.

People can and do seek to use government for their own personal purposes, but many others are also interested in helping make the entire community a better place to live and work. People may disagree about whether a proposal is in the public interest, and that type of debate is important. It is helpful to ask how the community would be better off if a proposal is adopted. This question focuses attention on the public benefits of government action. People who want the government to act should be able to explain how they think the proposed action will help improve conditions in the community.

Orange County Food Council

In 2015, a group of about 15 Orange County residents came together to create the Orange County Food Council (OCFC). The group included farmers, elected officials, chefs, and faith leaders, among others. They wanted to encourage local production of food that would be bought and eaten by people right in the county. The council determined that a “single point person” was needed to help the group achieve its goals. In 2017 the OCFC decided that a paid, full-time Food Council Coordinator position would make connections across the community and coordinate the council’s projects. Representatives from OCFC shared their ideas with Hillsborough, Chapel Hill, Carrboro, and Orange County governments. The four governments agreed to fund the position. The first OCFC coordinator was hired in 2019.

In just a few years the council accomplished a lot. It created a community food resource guide so people could find where to buy locally grown food. It established a composting program in Orange County schools. It created new partnerships to help people overcome barriers to getting locally produced food. And it served as a hub of communication and coordination for food distribution issues during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Food councils like the OCFC are being organized across North Carolina and the United States. Sometimes the impetus for these volunteer groups comes from local government leaders. More often it comes from passionate residents who find that they can work with local government to achieve goals that benefit the whole community.

Good government depends on the public being aware of the problems and opportunities facing the community. It requires that many people learn about public issues and try to influence public policy.

Voters

The voters in each jurisdiction choose the members of their local governing boards. The voters in each county also elect a sheriff and a register of deeds. The voters must also approve any agreement by their local government to borrow money that will be repaid with tax receipts. Through voting, the people determine who their government leaders will be and give the officials they elect the authority to govern. Voting is, thus, an essential part of representative democracy. Voting is both a very special responsibility and a very important civil right.

Struggles over the right to vote have continued ever since the United States gained independence from Great Britain. At independence, only free male citizens who were 21 years of age or older and paid taxes could vote for members of the lower house of the North Carolina General Assembly. Only men who met all these qualifications and owned at least 50 acres of land could vote for members of the state senate. (There were no local elected officials.) Most African Americans were held as slaves and could not vote at all. In 1835, the General Assembly prohibited even free men of African descent from voting in North Carolina.

After the Civil War, slavery was abolished and former slaves became full citizens. During the last third of the nineteenth century, African American men participated actively in North Carolina politics and were elected to state and local public offices, as well as to Congress. However, many whites in North Carolina continued to fear and disdain the former slaves (and the few Native Americans still living in the state). Near the end of the nineteenth century, a white majority in the General Assembly passed laws requiring segregation of the races. Nonwhite citizens were denied basic civil rights, and government officials even overlooked violence against them. By 1900, few of North Carolina’s African American or Native American men were able to vote or hold public office.

Women could not vote in North Carolina at the beginning of the twentieth century either, even though some people had long been seeking voting rights (or “suffrage”) for women. Finally, in 1920, the women’s suffrage movement was successful. That year the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution extended the right to vote to female citizens 21 and older.

Although white women began to vote in North Carolina in the 1920s, most African American and Native American citizens of North Carolina were prevented from voting until the 1960s. A major accomplishment of the civil rights movement, which also ended racial segregation in North Carolina, was the guarantee of voting rights for all adult citizens, enacted into law through the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The last extension of voting rights came in 1971 when the Twenty-Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution guaranteed the right to vote to younger citizens. Now, all citizens who are at least 18 years old are eligible to vote.

Being eligible to vote does not make you a voter, however. To be a voter, you must first register with the local board of elections in the county where you live. Seventeen-year-old citizens may register if they will be eighteen years old by the next general election. Thus, you can register and vote in a primary election when you are seventeen if your eighteenth birthday comes before the November general election.

To vote, you must also cast your ballot. Each county is divided into voting precincts. The county board of elections establishes a place to vote—a polling place—in each precinct. Registered voters may cast their ballots in person at the polling place on Election Day. Most county boards of elections also establish special “early voting” polling places where any voter registered in the county may vote during a period set by the state board of elections. Voters who find it necessary or more convenient may vote by absentee ballot.

People vote because they want to exercise their rights. They vote to support candidates, parties, or issues. They vote to oppose candidates, parties, or issues. They vote to make their communities better. They vote to show that the government belongs to them and because they feel responsible for helping to select public leaders.

Elected Officials

The elected leaders of local governments are the members of their governing boards. For counties, these are the county commissioners. For municipalities, they are the council members (sometimes called “aldermen” or “commissioners”) and mayor. These officials have the authority to adopt policies for local government and are responsible to the people for seeing that local government responds to public needs and works well to meet those needs.

The governing board is the local government’s legislature. The members discuss and debate policy proposals. Under state law, the board is authorized to determine what local public services to provide, what community improvements to pursue, and what kinds of behavior and land use to regulate as harmful. The local governing board also sets local tax rates and user fees and adopts a budget for spending the local government’s funds. In all counties and all but the smallest cities, the board appoints a professional manager. All of these are group decisions. Board members vote, and a majority must approve for an action to pass.

Each local governing board has a presiding officer—someone who conducts the meetings of the governing board, speaks officially for the local government, and represents the government at ceremonies and celebrations. In cities and towns, this is the mayor. Voters elect the mayor in most North Carolina cities and towns. In a few of the state’s municipalities, however, members of the local governing board elect a mayor from among the members of the board. The presiding officer for a county is the chair of the board of county commissioners. In most North Carolina counties, the board elects one of its members as chair. In a few counties, the voters elect the chair of the board directly.

The sheriff and the register of deeds are elected to head their respective departments of county government. The sheriff’s department operates the county jail, patrols and investigates crimes in areas of the county not served by other local police departments, and serves court orders and subpoenas. The register of deeds office maintains official records of land and of births, deaths, and marriages. Both the sheriff and the register of deeds hire their own staffs. They are not required to hire based on merit, although their employees must meet basic requirements set by the state.

School board members are also local elected officials. School boards are like city and county governing boards, except their authority is more limited. They are responsible for policies regarding the local public schools and they hire a superintendent to manage the schools, but they cannot set tax rates or appropriate funds. The board of county commissioners determines how much money the county will spend to support local public schools.

All local elected officials represent the people of their jurisdiction. People often contact these elected officials to suggest policy changes or to express their opinions on policy proposals that are being considered by the board. Boards hold public hearings on particularly controversial issues to provide additional opportunities for people to tell the board their views on policy proposals.

Altogether, more than 700 elected officials serve the state’s county governments and more than 3,200 serve in North Carolina municipalities.

Why do people run for a seat on the local governing board? They may be interested in getting local government to adopt a particular policy proposal. They may want to help shape the future of the community more generally. They may feel an obligation to serve the public. They may want to explore politics and perhaps prepare for seeking state or federal office. They may enjoy exercising public responsibility or being recognized as a public leader.

Elections for Local Offices

Elected officials get their authority from the people. Campaigning for office gives candidates an opportunity to express their views about local issues and to hear what citizens want from their elected officials. Elections give voters the opportunity to choose leaders who share their views on issues. Through elections, voters give elected officials the authority to make decisions that everyone will have to obey. Through elections, voters also hold elected officials accountable. People can vote against an elected official in the next election if they decide someone else will better represent them.

Elections are held every two or four years, depending on the term established for each office. In jurisdictions where board members are elected by district or ward, each voter votes only for the candidate from his or her own district. In jurisdictions where members are elected at large, each voter may vote for as many candidates as there are positions to be filled. Some jurisdictions have at-large elections for board members but require that candidates live in and run for seats representing specific districts.

Election by district may produce a more diverse governing board if minority groups are concentrated in some parts of the jurisdiction. Districts can be drawn around those population concentrations so that a group, which is a minority in the total population, is a majority within the district.

The right to vote is central to democratic self-governance, yet voting rates in local elections are almost always very low. For example, only 13 percent of eligible voters cast ballots in 2019 municipal elections in North Carolina. Nationwide voter turnout in local elections is usually around 20 percent.

- Why do you think voter turnout is so low in local elections?

- Given what you have learned about how local governments impact your quality of life, what reasons can you offer for voting in local elections?

Elections for county commissioners are held on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November in even-numbered years, along with elections for state officials and members of Congress. The county sheriff and register of deeds are also elected on this cycle. In practice, the sheriff and register of deeds are often reelected; it is common for them to serve until they choose to retire. Frequently their successors have served as their deputies. Sometimes, however, these elections are highly contested—especially elections for sheriff.

County elections are partisan. That is, candidates run under political party labels. Primary elections are held several months before the November general election. Primary elections are elections among the candidates of a party to choose the party’s candidates for the general election. In the primary election, members of each party vote only for their party’s candidate. Voters who have registered without indicating a political party can choose to vote in any one party’s primary. Candidates may also be placed on the ballot by filing petitions.

Elections for municipal boards are held in odd-numbered years. Election for mayors are held at the same time in those cities and towns where the voters elect the mayor. Most cities and towns have nonpartisan elections. That is, candidates do not run under party labels. These municipalities may have local voters’ organizations that support candidates, but parties are not permitted to run candidates in most North Carolina municipalities. Only a few cities and towns hold primary elections.

Most school board elections are also nonpartisan. School board elections can be in even-numbered years or odd-numbered years; this varies by county. Some counties have school board elections at the time of the general election, some at the time of the primary election, and some on special election dates.

Local Government Employees

Counties and municipalities hire many kinds of workers. Counties hire teachers, nurses, social workers, sanitation inspectors, librarians, and many other specialists to carry out county services. Similarly, cities hire police officers, engineers, machinery operators, recreation supervisors, and a wide variety of other specialists to carry out their services. Both city and county governments hire accountants, clerks, maintenance workers, administrators, and other staff to support the work of the government. These employees organize government activities, keep government records and accounts of public money, clean and repair government property, and pay the government’s bills.

Most North Carolina local governments have well-established systems for hiring employees based on their qualifications for the job. In some local governments in other states, people who work for local government get their jobs because of personal or political connections. Hiring based on kinship is called nepotism, hiring based on friendship is called favoritism, and hiring based on political support is called patronage. Most North Carolina local governments have and enforce rules against nepotism, favoritism, and patronage.

Local governments in North Carolina usually hire people who have the training and experience to do the job they are being hired for. This is known as hiring based on merit. Local governments in North Carolina hire people based on merit because their primary concern is having employees who can provide the best government services for the lowest cost. In a merit system, people are also promoted or dismissed based on their job performance, rather than for personal or political reasons.

Except in the smallest North Carolina municipalities, the governing board appoints a city or county manager who is responsible for hiring, promoting, and dismissing government employees. The manager serves at the pleasure of the board, meaning the board can fire the manager at any time should they decide to do so. The board evaluates the manager on how well services are provided and government funds are used. Thus, the manager wants to be sure local government employees are doing their jobs well.

In larger counties and cities, the manager assigns much of the work of hiring and supporting the government’s employees to a human resource (or personnel) department. To guide its work, the human resources department prepares job descriptions for all employees.

An employee’s job description lists the duties of the job. When a job becomes vacant, the local government uses the job description to advertise the position. The human resources department accepts job applications from people who would like to be hired for the vacant position. In filling out the job application, the applicant lists his or her education, job training, skills, and previous work experience.

The human resources department reviews the applications and selects the applicants who appear to be best qualified for the job. Applicants are often asked to provide the names of references. References are often asked about the applicant’s performance or work ethic. The final set of applicants is then selected and interviewed by people who would supervise their work if they were hired. Usually, the head of the department in which the new employee will work recommends who to hire.

Most local government employees enjoy their jobs and working for the public. They are honest, hard-working people who care about making their community a better place.

City and County Managers

City and county managers are hired by their elected boards to serve as the chief executives of the local government. In North Carolina, all counties and most cities with at least 2,500 residents employ a manger as chief executive of the local government.

A city or county manager is typically a professional who has studied public administration and belongs to the International City/County Management Association (ICMA) and the North Carolina City County Management Association (NCCCMA).

Each city or county manager:

- prepares a draft budget for the local government,

- manages the government’s expenditures,

- hires and fires other employees of the government,

- directs staff to carry out the polices the elected board adopts,

- reports to the board on government operations, and

- alerts the board to problems and opportunities facing the local government.

To assure democratic accountability, the elected board has ultimate responsibility for government policies and operation. The board hires the manager and the board can dismiss the manager by a majority vote at any time and for any reason. To provide some job protection to the manager, however, many managers and boards sign employment contracts. These typically require several months’ severance pay if the board fires the manager without a cause such as disobeying laws or policies.

Volunteers

Volunteers serve on many local government advisory boards and help carry out important public services. Volunteers fight fires, provide emergency rescue services, and assist in programs for children, youth, the elderly, homeless people, and other groups with special needs. Volunteers may be organized through a city or county’s fire department, recreation department, social services department, or other division of government. They may also be organized through a nonprofit organization that works in cooperation with local government.

Local government committees, boards, and commissions provide opportunities for many citizens to assist the elected governing board in shaping public policy. State law requires that alcoholic beverage control boards and boards of elections, health, mental health, and social services play a direct role in selecting agency heads and setting operating policies for the agency. Other boards are established by the local government to provide policy direction for airports, civic centers, public housing, stadiums, or other public facilities. Still other boards advise elected officials directly on matters ranging from the environment to human relations, from recreation to job training, and from open space to transportation, among others. Large cities and counties may have more than 30 appointed boards and commissions, with many hundreds of citizens serving in a volunteer capacity on those boards.

On some boards, at least some of the members must be appointed from specific groups in the community. For example, a mental health local management entity board must include, among others, a person representing the general public; a person with financial expertise; a person with health care expertise; and a family member of a person with mental illness, intellectual or developmental disabilities, or substance use disorder. Other boards or commissions may require that members be residents of various parts of the jurisdiction to provide broad geographic representation. County boards of elections must include both Democrats and Republicans, with the party of the governor having the majority of members.

People volunteer to serve on appointed committees, boards, and commissions for many reasons. Having a concern for the subject the board deals with is especially important for many volunteers. Appointed boards have a narrower range of concerns than city councils or county commissions. Appointed boards provide an opportunity for people with an interest in historic preservation, nursing homes, or another public policy area to work on policy for that particular concern.

Most of the unincorporated areas of the state and most small municipalities depend on volunteers for firefighting. Also, many counties rely on volunteer emergency rescue squads to provide medical assistance and rescue work. Like their full-time, paid counterparts, volunteer firefighters and emergency medical service technicians are required to have extensive training.

Many volunteer fire departments and rescue squads are organized as nonprofit corporations. They have contracts with a local government to provide fire protection to a specific area. The volunteer fire department receives public funds to buy equipment and supplies needed in fighting fires. Similarly, municipal and county governments often provide buildings or funding for emergency shelters, senior citizens’ centers, hot lunch programs, youth recreation leagues, and other services operated by nonprofit organizations and staffed by volunteers.

Volunteers assist local governments in making policies and carrying out services that help people and make their cities and counties better places to live and work. The wide variety of volunteer opportunities provides ways for everyone to contribute to the community.

Civic Engagement – Helping Improve Your Community

At the heart of the notion of people—within and outside of government—working together to help make their community better is civic engagement.

All of the people this chapter has discussed—elected officials, local government employees, and community volunteers, along with local businesses, churches, and other civic organizations—help make a difference in the overall quality of life through their actions (or inaction).

To be civically engaged means deliberately taking positive steps to make a difference. That could be as simple as remembering to sort your recycling and take it to the curb instead of throwing all your trash in the trash bin. But it could also mean volunteering to serve on an advisory committee or as a little league baseball coach. Civic engagement also involves learning about local government and knowing what is going on in your community. Attending public meetings, following your local governments’ social media accounts, and even talking to your neighbors about how you might improve your community, are all forms of civic engagement.

Local governments often reach out to residents in the community in efforts to help them be more engaged. Investing staff time to update social media accounts, for example, keeps the community informed and encourages participation in local government projects. Many local governments regularly survey residents to learn their satisfaction with service delivery or to solicit opinions on potential service changes. Some local governments offer free civic education programs, often called citizens academies, to their residents that cover all the main functions of the local government.

Citizens academies go by different names such as “Concord 101,” “Civics 101” or “Durham Neighborhood College.” Multiple sessions are taught by government staff. They often involve field trips to facilities like water treatment plants or recreation centers and tend to be hands-on and fun. Participants find that they not only learn a lot about their community and local government, but they also enjoy getting to know staff and making new friends. Many participants of citizens academies are inspired enough by their experience that they go on to volunteer for advisory committees or otherwise step-up their own levels of civic engagement.

Hear a participant’s experience attending the Fayetteville, N.C. Citizens Academy in this video on YouTube.

Hear a participant’s experience attending the Fayetteville, N.C. Citizens Academy in this video on YouTube.Law enforcement agencies also run citizens academy programs focused on public safety. Many sheriff’s offices and municipal police departments have programs that offer not only an opportunity to interact with officers, participate in “ride-alongs” and visit the county jail, but also encourage civic engagement through community policing or neighborhood watch programs.

Many local government leaders recognize the importance of youth civic participation and have developed specific engagement opportunities for middle and high school aged youth. Some communities, for example, have developed citizens academies specifically for youth, such as “Teen Morrisville 101.” Some municipal mayors have created mayor’s youth councils where a panel of (usually) high school students advise the mayor on youth issues and oversee youth-related projects. It is also not uncommon to find youth advisory boards or councils in counties and municipalities where youth can provide elected leaders their perspectives on issues and otherwise be directly involved in the governance of their communities.

Wherever you are, you live within the jurisdiction of a local government. You can engage with that local government as a voter, a volunteer, perhaps even as an employee or elected official, or just as a resident—someone who cares about the community—to improve the community and make it a better place to live. You will find many opportunities to engage if you look around. How will you make a positive in difference in your neighborhood, city, and county?

Take Action

✔ Find out who your local government elected leaders are. How long have they been serving? What are their backgrounds? How well do you think they represent your community? Why?

✔ Learn about city and/or county manager. What are their backgrounds and experience? How long have they served your community?

✔ Research the board of elections in your county. Who serves on that board? What can you find out about recent elections?

✔ Where can you find out about volunteer opportunities in your community? What opportunities to volunteer are most appealing to you?

✔ Does your county or municipal government offer a citizens academy? What about a public safety academy by the sheriff or municipal police department? If so, consider applying to participate if possible.

controlled distribution of scarce resources

a regularly held election for public offices

an election in which voters select candidates for a general election

the list of candidates on which people cast their votes

a geographic area that contains a specific number of voters

an official place for voting

an official list of candidates on which voters can indicate their votes without going to an official polling place

a section of a jurisdiction for voting, representative, or administrative purposes

involving political parties

an association of voters with broad common interests who want to influence or control decision making in government by electing the party’s candidates to public office

not affiliated with a political party

hiring or giving favorable treatment to someone based on kinship

showing partiality; favoring someone over others

hiring or giving favorable treatment to an employee because he or she is a member of one’s political party

hiring or promoting based on a person’s qualifications, ability, and performance

a person who knows how well someone did on a previous job or about that person’s other qualifications for a job

learning how and working to make a positive difference in the civic life of your community through political and nonpolitical efforts

civic education program facilitated by local government(s) for the purpose of informing and building positive relationships with residents and encouraging civic engagement